Abstract

Geopolitical tensions in the Indo-Pacific in 2026 reveal an increasingly pronounced strategic paradox: the weakening normative commitment of the United States to the rules-based international order on the one hand, and the growing dependence of its Asian allies on Washington as a security anchor on the other. Drawing on the Indo-Pacific Forecast 2026 discussion hosted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) on 14 January 2026, this article analyzes regional political, economic, and security dynamics by positioning the United States, China, Russia, and North Korea as key actors. Employing a juridical-strategic analytical approach, the article examines the root causes of regional tensions, their implications for international law, and policy options grounded in multilateralism and collective deterrence. It argues that regional stability in 2026 is fragile and tactical, while the risk of structural escalation continues to accumulate toward the end of the decade.

Keywords: Indo-Pacific, United States Alliances, China, Regional Stability, International Law, Rules-Based International Order

1. The Strategic Context of the Indo-Pacific in 2026 within the Global Geopolitical Landscape

The year 2026 marks a critical phase in the evolution of the Indo-Pacific security order, as regional dynamics can no longer be separated from simultaneous global crises, ranging from the protracted war in Ukraine since 2022, escalating conflicts in the Middle East, to the United States’ military intervention in Venezuela in early January 2026. In the opening session of the Indo-Pacific Forecast 2026 hosted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) on 14 January 2026, Victor Cha emphasized that despite Washington’s political attention being absorbed by multiple conflict theaters, U.S. strategic and economic interests in the Indo-Pacific remain fundamental and irreplaceable. This assertion reflects the reality that the Indo-Pacific has become the new gravitational center of the international system, both in terms of global economic growth and great power competition.

Structurally, the Indo-Pacific constitutes the world’s most economically dense region, accounting for more than 60 percent of global Gross Domestic Product and hosting strategic sea lanes that sustain international trade. Global dependence on regional stability renders any security development in the Indo-Pacific systemically consequential. From the perspective of international law, regional stability rests on the fundamental principles of the United Nations Charter, particularly the prohibition on the use of force under Article 2(4), as well as freedom of navigation and the peaceful settlement of disputes as enshrined in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). In practice, however, these principles are increasingly eroded by coercive practices and unilateral approaches.

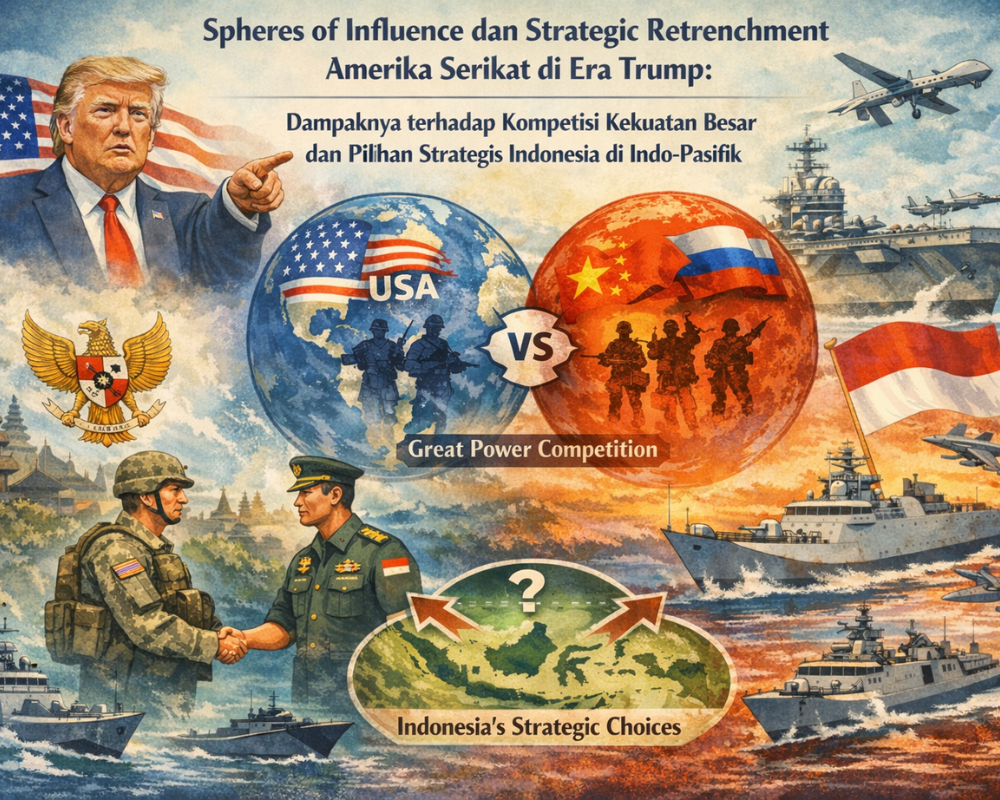

The central paradox of 2026 lies in the tension between the increasingly transactional nature of U.S. foreign policy behavior and the objective security dependence of East Asian states on Washington. Under President Donald Trump’s second term, the United States has openly displayed skepticism toward multilateralism, including international organizations and global legal regimes that have long underpinned American hegemony itself. Nevertheless, China’s assertive regional behavior has narrowed the strategic options available to Asian states, thereby reinforcing the United States’ position as the most credible balancing power.

CSIS discussions characterize the Indo-Pacific in 2026 as experiencing a condition best described as illusory stability. There are no strong indicators of imminent large-scale conflict, particularly open warfare between China and the United States. However, this stability does not stem from strategic reconciliation or resolution of underlying disputes, but rather from short-term political calculations and fragile economic interdependence. From an international legal perspective, this creates a dangerous gray zone, where the prohibition on the use of force is not overtly violated, yet is continuously tested through coercive military, economic, and diplomatic practices.

Accordingly, understanding the Indo-Pacific in 2026 cannot rely solely on the absence or presence of open conflict, but must focus on the accumulation of structural pressures that gradually undermine the rules-based international order. The region reflects the broader transformation of the international system toward an unstable multipolar configuration, in which international legal norms are increasingly treated as political instruments rather than as constraints on power.

2. Problem Analysis: U.S. Alliances, Chinese Assertiveness, and the Russia–North Korea Variable

One of the most consistent findings of the Indo-Pacific Forecast 2026 is the resilience of the U.S. alliance network in the region, despite serious uncertainty regarding Washington’s foreign policy orientation. Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and Australia continue to regard the United States as their primary security partner, not solely due to shared values, but because of increasingly tangible threat perceptions emanating from China. In this sense, Beijing’s behavior functions as a unifying force for U.S. alliances, a strategic irony demonstrating that alliance cohesion is often forged by external threats rather than ideological convergence.

Chinese assertiveness during 2025–2026 exhibits qualitative escalation, particularly in the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait. Chinese military activities are no longer confined to coast guard or maritime militia operations, but are increasingly dominated by the routine and structured presence of the People’s Liberation Army Navy. This shift reflects the normalization of military presence in disputed areas, a strategy that implicitly contradicts the obligation to settle disputes peacefully as stipulated in Article 279 of UNCLOS. Such practices weaken the international law of the sea regime without explicitly breaching its norms, complicating collective legal responses.

Taiwan remains the epicenter of strategic risk in the region. China’s large-scale military exercises in late 2025, known as Justice Mission 2025, involved more than 200 military aircraft sorties and approximately 30 warships and coast guard vessels, accompanied by live-fire missile drills. Although most CSIS analysts estimate the probability of significant military force being used against Taiwan in 2026 at below 20 percent, the risk remains high-impact. Under international law, any use of force against Taiwan would potentially violate the principle of non-intervention and threaten international peace, regardless of the complex legal debate surrounding Taiwan’s status.

Russia and North Korea serve as amplifying variables of instability, albeit in different ways. Russia, still entrenched in the Ukraine war, lacks significant independent capacity to shape Indo-Pacific security. However, its military cooperation with China, including joint exercises near Japan and the Korean Peninsula, reinforces regional threat perceptions. In this context, Russia acts as a strategic enabler for China rather than as a decisive actor, reflecting its shift into a junior-partner role within the global power configuration, a notable departure from its Cold War-era status as an independent great power.

By contrast, North Korea functions as a highly disruptive actor with elevated escalation potential. Pyongyang has achieved de facto nuclear power status and demonstrates a sophisticated ability to calibrate provocations. In an international environment marked by the declining effectiveness of the UN Security Council due to geopolitical fragmentation, North Korea no longer faces effective collective pressure. This development creates a dangerous precedent for the global nonproliferation regime, particularly the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, whose legitimacy is increasingly undermined by power-political realities.

Overall, the Indo-Pacific problem structure in 2026 reveals that regional stability is not sustained by compliance with international law, but by a balance of fear and short-term cost-benefit calculations. U.S. alliances endure not because of Washington’s normative leadership, but due to the absence of credible alternative security providers. This condition generates strategic dependence that is inherently fragile and heightens escalation risks should any major actor alter its calculations dramatically.

3. The Economic-Strategic Dimension of the Indo-Pacific: Trade Dependence, Technology, and Economic Weapons

Indo-Pacific security stability in 2026 cannot be understood without positioning the economic dimension as a central strategic variable. CSIS discussions underscore that open conflict is avoided not primarily due to international legal norms, but because of extreme economic interdependence among the United States, China, and East Asian states. China remains the largest trading partner for Japan, South Korea, and ASEAN countries, while the United States retains a central role in global finance, advanced technology, and maritime security. This interdependence creates an effective conflict restraint mechanism, albeit one that is fragile and instrumental.

U.S. trade policy under President Donald Trump’s second term exhibits increasingly overt protectionism. Plans to review tariffs on Chinese high-technology products in early 2026, including semiconductors, electric vehicle batteries, and artificial intelligence components, reflect the use of economic instruments as strategic pressure tools. Normatively, this approach conflicts with free trade principles under the World Trade Organization framework, particularly non-discrimination and most-favoured-nation principles, although often justified through national security exceptions under Article XXI of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

China has responded by strengthening import substitution and technological self-reliance through the expanded Made in China 2025 strategy and massive investment in domestic semiconductor industries. In 2025, Beijing allocated more than USD 150 billion to national chip development, signaling a determined effort to reduce dependence on Western supply chains. However, this accelerates global economic fragmentation into competing technology blocs, a trend that threatens the multilateral trade regime that has underpinned global stability since the end of World War II.

Indo-Pacific states face acute dilemmas amid escalating economic warfare. Japan and South Korea, as core U.S. allies, are bound by increasingly stringent technology export control regimes, particularly concerning advanced semiconductors and manufacturing equipment. Simultaneously, their industrial dependence on the Chinese market imposes substantial economic costs should decoupling be pursued aggressively. This dilemma illustrates that security alliances do not necessarily align with national economic interests, generating internal policy frictions among U.S. allies.

From an international legal perspective, the use of sanctions, tariffs, and export controls as coercive instruments raises serious questions about the boundary between lawful economic policy and non-military force that undermines the spirit of the UN Charter. Although not classified as armed force, such practices can substantially threaten stability and welfare, particularly for developing Southeast Asian states caught within global supply chain competition. Consequently, the Indo-Pacific economy in 2026 functions as a strategic battleground no less consequential than the military domain.

4. The Erosion of the Rules-Based International Order and Legal Challenges in the Indo-Pacific

The most critical dimension of Indo-Pacific dynamics in 2026 lies in the gradual erosion of the rules-based international order, particularly in public international law. While nearly all major regional actors rhetorically affirm commitment to the rule-based international order, policy practice increasingly reflects the instrumentalization of law for narrow strategic interests. This phenomenon signals a shift from law as a constraint on power to law as a legitimizing tool of power.

The United States, historically the principal architect of the post-1945 international order, exhibits growing normative ambiguity. Washington’s selective approach to international law, including its non-participation in UNCLOS and expansive reliance on national security exceptions, weakens its moral authority in demanding compliance from others. In the Indo-Pacific, this creates a strategic paradox in which the United States serves as guarantor of maritime security and freedom of navigation while remaining only partially bound by the legal regime underpinning those claims.

China, meanwhile, consistently rejects the 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling in Philippines v. China concerning the South China Sea, citing sovereignty and jurisdictional grounds. This rejection substantively contradicts UNCLOS obligations to accept and comply with final and binding arbitral decisions. China’s ability to sustain this position without significant consequences highlights the weakness of international law enforcement mechanisms in an increasingly fragmented international system.

Middle and small powers in the Indo-Pacific, including ASEAN members, are the most vulnerable in this context. Their reliance on international law to protect national interests is disproportionate to their capacity to enforce compliance by major powers. This widens the gap between norms and practice and increases the risk that international law is perceived as optional rather than binding. Over time, such conditions threaten the legitimacy of multilateral institutions, including the United Nations and its specialized agencies.

CSIS discourse emphasizes that while major military escalation may be avoided in the short term, ongoing normative degradation creates more dangerous strategic conditions. Without a robust legal foundation, regional stability depends entirely on power calculations and political intentions. Juridically, this contradicts the primary purpose of international law as articulated in the Preamble of the UN Charter: to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war.

Thus, the Indo-Pacific in 2026 reflects a structural, not incidental, crisis of international legal legitimacy. The principal challenge ahead is not merely preventing armed conflict, but restoring international law’s function as a framework for conflict management and equitable power distribution. Without collective efforts in this direction, the Indo-Pacific risks becoming a laboratory for the normalization of global norm violations.

5. Strategic Solutions: Adaptive Multilateralism, Collective Deterrence, and the Role of Middle Powers

Responding to Indo-Pacific dynamics in 2026 marked by escalating great power rivalry, economic fragmentation, and normative erosion requires strategic solutions that move beyond a binary opposition between legal idealism and power realism. What is needed is adaptive multilateralism, a collective approach rooted in international law yet capable of adjusting to shifting global power distributions. Adaptive multilateralism positions international institutions not as symbolic forums, but as practical mechanisms for conflict management, de-escalation, and confidence-building amid strategic uncertainty.

In regional security, collective deterrence remains relevant but must be interpreted more broadly than military prevention alone. Deterrence in 2026 encompasses military, economic, technological, and normative dimensions simultaneously. The presence of U.S. and allied forces in the Indo-Pacific, including through alliances such as NATO’s expanding strategic focus on Asia, signals security commitment. However, without credible legal and diplomatic frameworks, deterrence risks fueling mistrust spirals and strategic miscalculation, particularly in the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait.

Herein lies the critical role of middle powers. States such as Indonesia, Japan, Australia, and South Korea possess unique capacity to bridge major power interests without succumbing to zero-sum logic. Indonesia, as the world’s largest archipelagic state and an active ASEAN member, holds a direct stake in maritime stability and the supremacy of the law of the sea under UNCLOS. Indonesia’s formally non-aligned yet actively multilateral posture provides strong normative legitimacy to promote region-wide security dialogue grounded in international law.

ASEAN, though often criticized as slow and consensus-driven, remains an essential platform for managing Indo-Pacific tensions. Through mechanisms such as the ASEAN Regional Forum and the East Asia Summit, regional states can address security issues inclusively, engaging the United States, China, and Russia. ASEAN’s core challenge lies not in institutional absence, but in political consistency to reaffirm foundational principles of non-intervention, peaceful dispute resolution, and sovereignty, as reflected in the ASEAN Charter and the UN Charter.

Strategic solutions further require strengthening international legal norms through consistent state practice. States that rhetorically support the rule-based international order must demonstrate tangible compliance with international court rulings, multilateral treaties, and dispute resolution mechanisms. Without exemplary conduct by major actors, efforts to sustain a rules-based order will lose legitimacy and effectiveness.

6. Policy Action, Strategic Conclusion, and Global Risk Projection

Implementing strategic solutions for the Indo-Pacific in 2026 demands concrete policy actions beyond political declarations. At the global level, the United Nations remains the principal pillar for maintaining international peace and security, despite structural limitations, particularly within the Security Council. Strengthening the role of the UN General Assembly as a forum of normative legitimacy, including through resolutions reaffirming international law supremacy, is essential to offset executive-level political paralysis.

At the regional level, Indo-Pacific states must promote more substantive confidence-building measures, particularly in maritime and aerial domains. Transparency in military exercises, crisis communication, and behavioral rules at sea, as pursued through the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea, should be expanded and reinforced. These measures derive legal grounding from conflict prevention principles and the obligation to resolve disputes peacefully under Article 2 of the UN Charter.

Within its free and active foreign policy framework, Indonesia holds strategic opportunity to exercise normative leadership. By leveraging its credibility within ASEAN and global forums such as the G20, Indonesia can advance an Indo-Pacific security narrative oriented toward collective stability and shared prosperity rather than bloc confrontation. Strengthening maritime diplomacy, asserting Exclusive Economic Zones under UNCLOS, and consistently rejecting the use or threat of force form the foundation of nationally relevant policy action.

In conclusion, the Indo-Pacific in 2026 stands at a historic crossroads between fragile stability and structural escalation. While large-scale armed conflict may be avoided in the short term, the convergence of great power rivalry, economic fragmentation, and normative degradation creates systemic risks that cannot be ignored. International history demonstrates that gradual rule erosion often precedes open conflict rather than prevents it.

Therefore, the central challenge for the international community is not merely preventing war, but restoring confidence in international law as a mechanism of power management. The Indo-Pacific is not only the arena of 21st-century strategic competition, but a critical test of the world’s capacity to sustain a just, stable, and rules-based international order. Success or failure in this region will shape the trajectory of the international system for decades to come.

Note;

The author, Dr. Surya Wiranto, SH MH, is a retired Rear Admiral of the Indonesian Navy, Advisor to Indo-Pacific Strategic Intelligence (ISI), Senior Advisory Group member of IKAHAN Indonesia-Australia, Lecturer at the Postgraduate Program on Maritime Security at the Indonesian Defense University, Head of the Kejuangan Department at PEPABRI, Member of FOKO, Secretary-General of the IKAL Strategic Center and Executive Director of the Indonesia Institute for Maritime Studies (IIMS). He is also active as a Lawyer, Receiver, and Mediator at the Legal Jangkar Indonesia law firm ⚓️.

References

- Charter of the United Nations, 1945.

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 1982.

- North Atlantic Treaty, 1949.

- World Trade Organization, General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, 1994.

- Permanent Court of Arbitration, The South China Sea Arbitration (Philippines v. China), Award of 12 July 2016.

- Center for Strategic and International Studies, Indo-Pacific Forecast 2026, Washington D.C., 2026.

- International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook 2025, Washington D.C., 2025.

- ASEAN Charter, 2007.

- White House, National Security Strategy of the United States, 2025.

- Indo-Pacific Forecast 2026, CSIS Live Event, 14 January 2026.